I Hate Lines

On Impatience, Democracy, a Better Tomorrow, and A Better Today.

I have hated lines since I can remember having to stand in one. Maybe I’ve always been impatient, and a little bit bougie.

It’s manifested in a number of ways — when I order movie tickets, I always reserve my seats so I can show up whenever and walk directly to my seat. When I go to a restaurant, I look up the menu hours ahead of time so that as soon as the waiter greets our table, I’ve already spent all my time deliberating, and I can give them my order as soon as it’s appropriate.

This was at its worst my senior year of college. As a fresh 21-year-old, a few friends of mine created a music blog to talk about pop culture and new albums. I emailed all the clubs in Boston claiming that our blog was going to review them and asking to be put on the list for consideration. I got on the list for every club in Boston with that system — and never even wrote the article.

In the last fiscal quarter, two Hinge matches told me on a first date that I am probably too bougie for us to work out long term. I think my visceral hatred for lines came from my mother more than anyone else.

Every first Tuesday of November, for as long as I can remember, my mother would wake me up around 5:30 in the morning. We would drive to the voting booth. I would ask, with crust in my eyes, red with exhaustion, wielding a milk-chug chocolate shake like Excalibur, “Why do we have to get up so early?”

And my mother would say, cheery as day, “We need to go vote! And I don’t want to wait in the lines.”

We would get to the booth, and I would stand on her shoes as she pointed out which ballot to pick. Then I would do the physical act of pulling the massive lever to submit her votes. I think some of her joy of voting transferred to me because to a child, to pull a lever or press a button is just as fun.

I don’t think my mother, a woman of remarkable patience, hates lines like I do. I show up early to avoid the line because I detest having to wait for anything. She shows up because she has great pride and joy in the civic duty of voting and won’t let a line be a hindrance to that joy.

When I reached voting age, I don’t think I felt the same joy or duty. I do vote. I think I should. But I often approach it with apathy.

I feel the same way about voting as I do about eating vegetables: it’s a bit of a chore, never feels great, but you have to do it to have a healthy body. Or a healthy democracy. Yet it’s still only one cog in a machine that has to be paired with exercise, education, staying hydrated, protesting, getting enough sunlight, and caring for your neighbors.

Part of this has to do with the politicians that have been available to me as a legal adult. My mother’s generation had the exciting political prospects of Shirley Chisholm, Al Gore, and, dare I say it, Barack Obama. They also didn’t have the internet to expose them to the total sum of who someone is beyond their public appearances.

When I was 12 years old, I sang the National Anthem at the first Nets game at the Newark Prudential Center with the Newark Boys Chorus School. We met Cory Booker, the then-mayor of Newark, New Jersey, and I was excited by the charismatic Black man who took time to shake the hands of every single student there.

When Barack Obama won in 2008, I found out because I was sitting at the desktop computer in the office playing Lilo and Stitch’s Sandwich Stacker on DisneyChannel.com. I heard my mother and father scream from the other room.

The first Black president. In the United States?

My father, and the majority of my aunts and uncles, are older than Ruby Bridges. This means they are older than the first student to ever attend an integrated school. So the election of a Black president, nearly 50 years later, represented a new world with precious unprecedented optimism.

I walked with my then 90 year old grandfather, at the cusp of my tragic fedora middle-highschool fedora phase, to the lawn of the U.S Capitol to see the first Black President be elected. My whole family came and we cheered louder than any one else in DC.

Me and Grandaddy (Charles Bentley) at President Obama’s first inauguration, caught on a flip phone.

Now when I see Cory Booker, I see a man who consistently votes for the genocide of Palestinian people while grandstanding, crafting public performances about how much he cares about democracy — a liar and a hypocrite hiding behind a fake smile.

When I see President Obama, I think not of the young charismatic progressive who “literally ended racism” (which is who I thought he was), but of a war criminal whose first strike on Yemen killed 55 people, including 21 children — 10 of whom were under the age of five.

Without letting this preamble get away from me, all this is to say that this morning I woke up at 5:40 in the morning to be first in line at the voting booth at 800 Gates Avenue.

For the first time in nearly a decade, the second time in my life at all, I felt like my mother. I was not apathetic about voting. I couldn’t wait to vote for Zohran Mamdani.

There are so many qualities that make Mamdani an exceptional candidate to me — his dedication to listening as opposed to speaking, his natural charisma, his youth and excitement — but most of all, his policy platform that is coherent and research-founded.

His policies address the roots of issues, not the symptoms.

I think the most important thing is that unlike voting for Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, or even Kamala Harris — the definitive elections of my adult life — voting for Zohran gave me something to vote for, not against.

Voting for the others felt like damage control. The tagline of every major election of my life has been “Lesser of Two Evils,” and if that’s our standard, why do I need to engage with evil at all?

Most recently, Kamala Harris got my vote not because I thought she was a great candidate but because she was not Donald Trump.

But she had a shoddy record when it came to policing and, frankly, an abysmal approach to Gaza — unambiguously the most heinous moral crime of modern times. Despite her potential voters nearly begging her to take a humanitarian position on the issue, she, just like Obama, could not separate herself from imperialism.

And I think that’s why she lost — because her vision was status quo and didn’t offer anything new or valuable to the United States.

Kamala Harris is now promoting her new book 107 Days, where she defends not having a gay man on the ticket.

“Part of me wanted to say, Screw it, let’s just do it. But knowing what was at stake, it was too big of a risk. And I think Pete also knew that — to our mutual sadness.”

The audacity to call a gay man “too much of a risk” while being someone the world has called both a “nigger” and a “bitch” is hilarious to me.

Democrats have always said “Not yet,” “We can’t,” or “That’s too much,” while Republicans plunder democracy in the same way a toddler reaches into a chest of action figures — no care, no regard, borderline violent because the toys have no life.

Mamdani came in with a cohesive plan for NYC. He focused on a future where every idea is possible with the political will to do it — not out of reach, navigating a wave of bureaucracy.

I often wonder why right-wing ideas have such widespread appeal. To me, so many right-wing actors are clearly acting in bad faith, promoting disingenuous and ahistorical reductions of every issue. But that is why they win.

Because they take complex problems, present simple solutions, and then ridicule anyone who insists it’s more complicated — all in the name of “common sense.”

When you tackle the idea of trans people, there are decades of research proving trans people have always existed and that biology, sex, and culture go beyond what’s in our pants. But conservatives boil it down to: men can’t be women and women can’t be men.

And that feels like common sense.

When it comes to Black people, a Charlie Kirk type can say, “Black people are 13% of the population but commit 58% of the murders. The issue has to be Black culture!” — and then move on without any substantive study into whether that claim is even valid, or what conditions would produce a claim like that: redlining, slavery, broken-windows theory, or Ronald Reagan.

When issues exist in grey areas, conservatives do a great job of selling the black and white.

Zohran Mamdani uniquely addresses issues in a simple, calm, and effective way — speaking to New Yorkers about the core of their hardships and delivering a straightforward plan to combat them.

While Andrew Cuomo and Curtis Sliwa both support increasing the police force by more than 5,000 officers, Mamdani has rejected the premise that more police make more people safe. He has proposed creating a Department of Community Safety — an organization dedicated to the prevention of violence and crime, not just the reaction to it.

This is one of his many policies that support legitimate reform rather than punishment and mass incarceration.

It’s something all budding progressives should learn from and embrace: speak to the core of an issue, and deliver a simple plan to address it.

I have no shame admitting I’m terminally online. I often scroll through the pages of Twitter reading what everyone has to say about anything, and I’m currently seeing leftist peers criticize Mamdani for not being left enough.

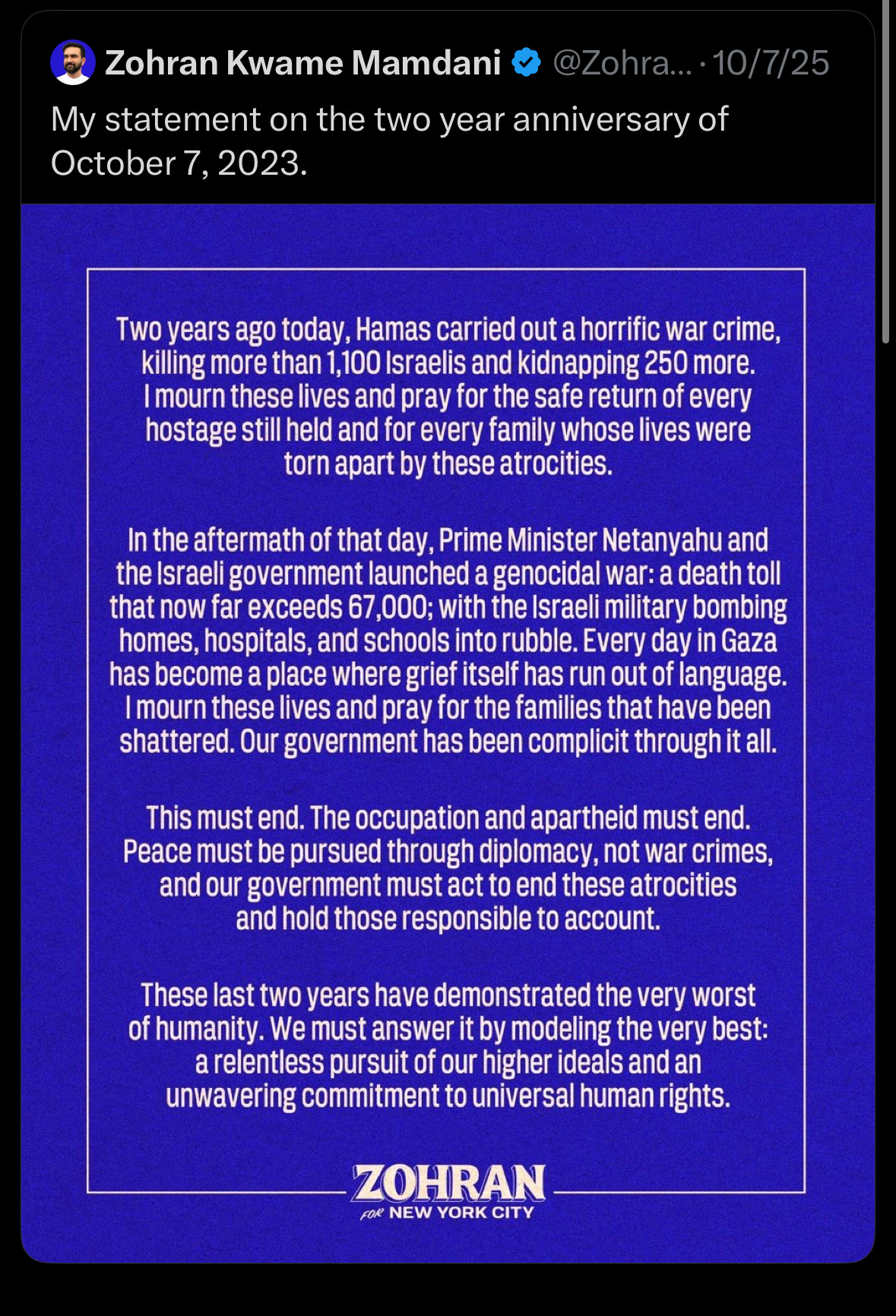

In particular, his statement on the anniversary of October 7th angered lots of people and, to be honest, bordered on misinformation. There’s justification in the critique — the omission of the word “Palestinian” is upsetting — but I do think we need to take a second and think about the roles that we occupy.

Zohran Mamdani is running for mayor. We have witnessed over the course of his career, even in the last year, that his rhetoric on certain issues has softened. But he is a politician, and the role of the politician is different from the role of the writer, the activist, the musician, or the protester.

Politics is only one piece of this journey, and as a mayoral candidate he does not have the freedom to be as critical as the activist does.

“That’s a separate thing from why politics happen the way they do... We don’t all have the same role. When I wrote The Case for Reparations, it was not my expectation, nor did I even think it would be politically intelligent, for Barack Obama to go up and yell: I’m for reparations. But that’s different than my role.”

— Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Ezra Klein Show, September 2025

Like eating vegetables, politics is just one aspect of the journey we’re on. And I think it’s important to note that while Zohran Mamdani has relaxed some of his rhetoric, his policies have remained the same. My hunch is that his heart has remained the same.

It is entirely probable that down the line, as he grows as a political force, his voting record will eventually disappoint his most leftist constituents.

But I think, as of now, when we have a talent so dedicated to the betterment of all people of NYC, we should support, care for, and uplift him — while being realistic about the limitations of the office.

And if the day comes when we’re disappointed, it’s well within our rights — nay, our duty — to be vocally critical.

I hope that tonight I’m toasting champagne with friends when his victory is announced, and I get to participate in joy the same way my parents did when President Obama won his first election.

I still hate lines. That’s not changing.

I hope my impatience is contagious.

Fannie Lou Hamer once said “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Maybe I hate lines because I’m done waiting for a better tomorrow and will work my damndest for a better today.

I hope that Zohran Mamdani’s journey is one of integrity, progress, and constant education. But also, I know that he’s only one cog in a machine.

Just like exercise.

Like education.

Staying hydrated.

Taking to the streets.

Getting enough sunlight.

Caring for your neighbors.

Zohran Mamdani is one exciting cog in this machine toward a better world.

The other cog is you. Is me. Is us.

And what we do tomorrow.